Exhibitions from the Museum Collection

What Your Eye Declares Is True: The Art of Charles C. Burleigh, Jr.

curated by Martha Hoppin

|

Northampton artist Charles Burleigh died in Germany in 1882, at the threshold of a promising career. He had spent four years studying and painting in Germany, his art had matured, and he had begun to exhibit in the national arena. But because death came at such a young age—only thirty-four years—and in a foreign country, his achievement did not receive the attention it deserved. Today, it is possible to tell his story more fully through the extensive collection of letters, sketches, and paintings donated to Historic Northampton by Burleigh family members. These reveal Burleigh’s passionate belief in the power of art and ideas, as well as his pragmatic resourcefulness in pursuing his goal.

|

Charles C. Burleigh, Jr., came from a distinguished family of free thinkers who nourished his artistic talent. His father was a prominent lecturer, author, and ardent abolitionist. His mother, Gertrude Kimber Burleigh, a Quaker from Chester County, Pennsylvania, was active in the anti-slavery movement and other political causes. Uncles and aunts lectured on temperance and wrote poetry. Two younger cousins also became artists. Education was another long-time interest of the Burleighs. Rinaldo Burleigh, grandfather of Charles Jr., was principal of Plainfield Academy. Gertrude Kimber’s family operated a boarding school in Pennsylvania. At right is a daguerreotype portrait of Gertrude Kimber Burleigh and Charles C. Burleigh, Sr. taken circa 1850.

Burleigh Jr. was born in 1848 in Pennsylvania but spent his childhood in Plainfield, Connecticut, his father’s birthplace. The Burleighs had two other children, Edward, born in 1846, and Teresa, born in 1851. The family moved to Florence, Massachusetts, in 1861. Two years later Charles Sr. became the first resident speaker of the newly formed Free Congregational Society of Florence, a remarkably liberal religious group. Charles Jr. met many prominent anti-slavery, temperance, and women’s suffrage figures of the period. During these early years he attended school and drew as much as possible. He produced a number of town views, including one of Florence that was issued as a lithograph by a Hartford firm about 1865. By the time he was eighteen, his artistic ability had earned local recognition, and he was readily admitted to the free drawing classes at the Lowell Institute in Boston.

For two academic years, 1866-1867 and 1867-1868, Burleigh studied drawing at the Lowell Institute under George Hollingsworth and William Carleton. The Lowell program was unusual in always having students draw from “the round,” rather than start by copying flat images like engravings. The class met two days a week in the evenings. Burleigh’s diary documents his efforts to render first a box, then a ball, and finally, by the second semester, a vase. He did so well during his first months that he was offered a job in Bufford’s lithographic firm, the training ground for a number of American artists including Winslow Homer. Both Hollingsworth and Carleton advised against it, urging him to continue his studies. Burleigh also found a patron soon after he arrived in Boston. As he was sketching the “old fashioned & very beautiful” home of “Col. Lee,” he reported, Mrs. Lee came out and not only bought the work, but commissioned several more views of the property.

At the beginning of January 1867, Burleigh added painting lessons with Carleton, and in his second year painted almost daily in Carleton’s studio. By that time Burleigh had also progressed to the evening life drawing class. He kept up a busy schedule with other activities like drawing and painting on his own, attending lectures, reading about art, and frequenting local art galleries (the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, had not yet opened). He had some contact with Boston artists, some of them Lowell Institute students, such as portraitist Frederic Porter Vinton and marine painter William E. Norton. Burleigh liked these men but disapproved of their smoking and swearing.

For his first year of study Burleigh lived in Jamaica Plains with the family of Edward Magill, then Submaster at Boston Latin School and soon afterwards president of Swarthmore College. Magill had grown up a Quaker in the Philadelphia area and must have had a family connection to Burleigh’s mother that led him to take in the young artist. Magill facilitated Burleigh’s admission to the Lowell Institute and promoted his work. It was through Magill’s efforts that Burleigh caught the attention of Bufford, the lithographer. It may also have been through Magill that Burleigh later received commissions from Andrew White, president of Cornell University, for copies of Old Master paintings in German museums. To earn his board, Burleigh worked for Magill, helping with the preparation of a book on the French language. As grateful as he was to Magill, Burleigh expressed frustration that he could not devote all his time to art study. By his second year in Boston, Magill had gone to Europe, and Burleigh boarded on Charles Street in Boston. He expressed a strong desire to work as hard as possible, both for his own ambitions and because his father was paying his expenses.

At the end of his Boston stay, Burleigh felt he was “getting on in quite a satisfactory manner” with his work. Nevertheless, he studied further, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He enrolled in the Life class for the months of February, March, and April of 1870. Presumably he chose this school because his mother’s family lived in the Philadelphia region. Her death only six months before may have precipitated his sojourn there.

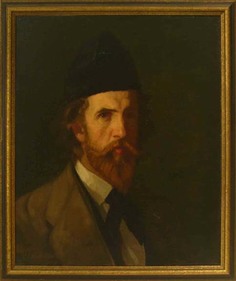

Except for the spring of 1870, Burleigh remained in Florence, Massachusetts, and set about establishing his career. He announced the opening of his studio and his readiness to accept pupils. He filled sketchbooks with landscape and architectural studies executed in sure pencil strokes and produced wash drawings, as well as oil paintings, of local views. He also painted portraits, of local notables like L. Clark Seelye, president of Smith College, and Pliny Earle, superintendent of the Northampton State Hospital, as well as of friends and family members. Some of his finest portrayed Florence Aldrich and her sister Ida. Charles Burleigh eventually married Ida, and his brother Edward married Florence. These personal paintings show Burleigh’s favorite composition: a bust length view, plain background, strong light casting faces in half shadow, and few accessories. Soft edges and deep shadows suggest thoughts and emotions. Visible, even loose brushwork defines clothing and highlights faces. A full-length portrait of Florence Aldrich shows the dark impressionistic style Burleigh had developed by 1878, at least for private portraits. For commissioned portraits, such as that of Pliny Earle, he may have employed more even lighting techniques for more straightforward likenesses. He must have had some success, for about 1875 he moved his studio to the Jones Block in Northampton, where he welcomed sitters, pupils, and anyone wishing to see his work on display.

During the mid-1870s, Burleigh also pursued a commercial avenue for his work. He had long made town and architectural views a staple of his drawing activity. Now he teamed up with artist Elbridge Kingsley to produce local views printed by the Star Printing Company of Northampton. Kingsley, a Hatfield native, moved to Northampton from New York in 1872 to work for the Star firm. As he recalled in his autobiography, Burleigh soon became his “constant companion.” They sketched together often in the local landscape. At one point they camped on Mt. Toby for days to draw and paint. Burleigh helped Kingsley, a wood engraver by training, learn the techniques of oil painting. Kingsley described many Burleigh landscapes, including views of the Oxbow and the Northampton meadows, which remain unlocated. During this period Burleigh produced lithographed views of the silk mill in Florence and of the First Church in Northampton from the town hall.

In addition to all these artistic activities, Burleigh also carried out a major project—designing mural decorations for Cosmian Hall, built in 1874 as the home of the Free Congregation of Florence. Although Cosmian Hall no longer stands, photographs give some idea of Burleigh’s frescos. These combined geometric and floral elements to create a light, airy atmosphere in the style of Roman wall paintings. One of Burleigh’s most successful drawings records the houses that stood on the future site of Cosmian Hall.

On September 2, 1878, Burleigh married Ida Aldrich. Like his family, hers was involved in teaching and came to Florence around 1876 because of a new educational experiment there—the first kindergarten. Ida, her sister Florence, and their mother Auretta, may all have taught at one time in the kindergarten established by Samuel Hill. Mrs. Aldrich became a respected authority in the field of childhood education and the author of several books on the subject.

Immediately after their wedding, the couple sailed for Europe, settling in Munich for the next year. Burleigh chose Munich for several reasons. Andrew D. White, president of Cornell University, had commissioned him to copy a number of paintings in Munich art museums. Artists of the period routinely made copies, as part of their training and as a means of earning money. Many American collectors bought copies of European “Old Masters” for display in their homes or local institutions. White ordered copies of works by such artists as Anthony Van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens, but he was also interested in modern German historical painters like the realist Karl Piloty. For example, Burleigh copied Piloty’s Death of Galileo for White. Having studied in Berlin, White had a special attachment to Germany and later served as United States Ambassador there. Why he selected Burleigh is not known, but the recommendation probably came about through education circles, perhaps from Edward Magill or L. Clark Seelye.

In the 1870s Munich was one of the most popular destinations for American artists. They studied at the Royal Academy, where Piloty was director and Wilhelm Diez a prominent teacher. The year Burleigh arrived, there were forty-two American students at the Academy. Burleigh enrolled in drawing classes for both the fall of 1878 and spring of 1879. Ida described his strenuous schedule: drawing class from 7:30 in the morning until noon, and again from 2:00 till 4:00; lectures four days a week from 4:00 till 5:00; life drawing class from 5:00 till 7:00. In addition to the Academy teachers, a second German artist in Munich, Wilhelm Leibl, had an important American following. Both Leibl and Diez favored spirited, open brushwork of the kind usually associated with sketches. Frank Duveneck, the leader of the American artists in Munich while Burleigh was in residence, painted with the vigorous technique and dark palette that came to define the Munich School. That Burleigh absorbed the Munich style is best seen in his freely painted portrait of his German landlady.

Burleigh already knew one of the most prominent American artists of the Munich group, J. Frank Currier. Slightly older than Burleigh, Currier had spent summers in Deerfield, Massachusetts, and may have met Burleigh then. Currier also attended the Lowell Institute, and Burleigh mentioned seeing him in Boston in 1867. In the summer of 1868, Currier wrote Burleigh from Deerfield to arrange a sketching date. Two years later, Currier moved to Munich. He was there to greet the Burleighs on their arrival and took them first to Polling, a village thirty-five miles south of the city. Many of the American artists summered in an old monastery there. Ida’s letters home describe these living/working quarters, where she and her husband stayed about ten days. She marveled at finding such a cultured environment at Polling. “Of course I am speaking of the little circle of artists that constitute what they have jokingly named the Polling Academy. Mr. Currier seems to be an accepted authority among them and it may rightly be called the Currier School.” Burleigh spent his time sketching in the countryside with Currier. Currier helped them find rooms in Munich, and he and his wife remained friends and mentors of the Burleighs. When Ida unexpectedly became pregnant, it was the Curriers who found a midwife and smoothed her adjustment to new customs. The Burleighs’s only child, Gertrude Kimber, was born on June 23, 1879, in Munich.

How long Burleigh stayed in Munich is not certain, but by January of 1880, he and his family were living in Dresden. He was studying at the Dresden Academy, filling more orders for copies, and painting portraits of his wife and his mother-in-law, who had come for an extended stay. That year he also began submitting his paintings to the annual exhibitions of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. His brother Edward now lived in Philadelphia and could serve as his agent. In all, eleven of his paintings were shown there. One of them, Portrait of a Lady, earned praise from the eminent critic Marianna von Rensselaer, writing for American Architect and Building News in 1881.

In May 1880 Burleigh received an important commission from an Englishwoman named Mrs. Davidson, who saw him at work in the Dresden art museum. She bought that painting—a copy of a Correggio—and ordered several more, in addition to a portrait of her son. Both Mrs. Davidson and Andrew White also asked Burleigh to copy works in Berlin, so in late October, the Burleighs moved to that city. They stayed for most of the next year. March and April of 1882 found them once again in Dresden. For the summer they went to Holland, and that fall to Cologne. All the while, it was the copying business that determined their travels, as Andrew White had requested more pictures. With orders from White for copies in Italian museums, Burleigh planned to go to Florence, but illness prevented the trip. He died December 5, 1882 in Cologne and was buried in nearby Ehrenfeld, where the family had been living.