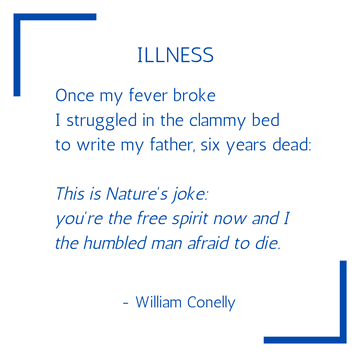

William Conelly

I'm 76 and we still have acreage in Leverett, where we lived for 20 years. It was in Leverett in fact, along Montague Road, that I wrote "Illness" after a particularly rough bout of the flu.

Amy Langdon

March 30, 2020 4:47pm

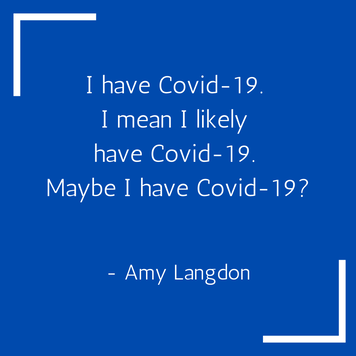

I have Covid-19.

I mean I likely have Covid-19.

Maybe I have Covid-19?

I don’t actually know because I can’t get tested. There are only tests for people who are hospitalized and my symptoms “aren’t that serious”. (Which as we all know isn’t totally true.... but I’m neither rich nor famous so no test for me)

I have a cough, body aches, a tightness in my chest, and a low-grade fever. My doctor says those symptoms track with others in my age group. She is tracking symptoms because that’s all she can do. I was given Tamiflu 5 days ago in case I had a regular flu and that hasn’t helped. When I told her I already had the flu this year she said, “oh dear” but did the best she could to prescribe what she could anyway.

I haven’t seen my kids in over a week. They are with their dad and I’m lucky enough to have that option. My husband brings in food and leaves it on the dresser and talks to me a few times a day from the doorway. I Zoomed with the best friends a girl could ask for yesterday and I’m constantly texting others. I’m catching up on reading and TV and movies and I’m working from home.

I’ve been alone in my bedroom for 5 days. I will be here anywhere between 2-4 more weeks until I am “100% better and can’t infect anyone else” as my doctor ordered.

I’m lucky. I know I’m lucky. It doesn’t mean I don’t cry every day because this sucks. It sucks so much.

And I’m one of the lucky ones.

April 3, 2020 4:54pm

Day 9 of symptoms:

Fever, cough, shortness of breath (not like I went for a run but like I went for a long, hard walk)

Just talked to my doctor: day 9-11 are the worst for people with symptoms like mine. The shortness of breath is common for day 9. Today and tomorrow will likely be the worst of it. She would expect that if this stays a mild case that I would start to feel better after the weekend.

After the fever AND cough are done it’s still three days before I can come out of isolation.

Still no testing. Maybe next week she said.

But she also said that she is nearly certain that I have it.

So for all of those numbers out there of confirmed positive cases, just know that there are hundreds? thousands? of others out there that aren’t counted because we can’t get tested.

April 7, 2020 1:05pm

Day 13:

Fever: 99°

Cough: Persistent

Breathing: Slightly labored

Sleeping: not well

Feelings: exhausted

Sunshine: beautiful and warm ️

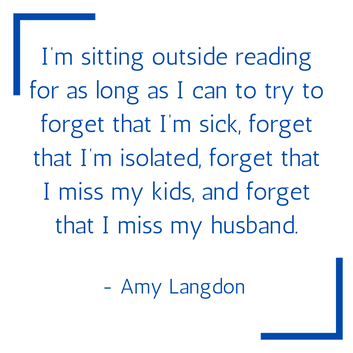

I’m sitting outside reading for as long as I can to try to forget that I’m sick, forget that I’m isolated, forget that I miss my kids, and forget that I miss my husband.

Today is just a beautiful, sunny day.... covid will still be there tomorrow....

April 8, 2020 8:22pm

Day 14:

Today was not a good day. I feel awful, my cough is worse, my fever is persistent, and my breathing is consistently slightly labored.

I thought I would be done with this by now.

I had another telehealth appointment today and was given an inhaler. They are testing: for those in the high-risk categories and those over 65. I was told if my breathing gets worse, go to the ER.

I’m scared of the ER.

My daughter cried today over FaceTime “Mommy I *need* you”

I have a follow up appointment on Friday.

Until then.... stay home, stay safe.

You do not want this. Even a “mild” case means complete separation from your family and worry that you might have gotten someone else sick.

Someone who might not be as lucky as you.

Day 13:

Fever: 99°

Cough: Persistent

Breathing: Slightly labored

Sleeping: not well

Feelings: exhausted

Sunshine: beautiful and warm ️

I’m sitting outside reading for as long as I can to try to forget that I’m sick, forget that I’m isolated, forget that I miss my kids, and forget that I miss my husband.

Today is just a beautiful, sunny day.... covid will still be there tomorrow....

April 8, 2020 8:22pm

Day 14:

Today was not a good day. I feel awful, my cough is worse, my fever is persistent, and my breathing is consistently slightly labored.

I thought I would be done with this by now.

I had another telehealth appointment today and was given an inhaler. They are testing: for those in the high-risk categories and those over 65. I was told if my breathing gets worse, go to the ER.

I’m scared of the ER.

My daughter cried today over FaceTime “Mommy I *need* you”

I have a follow up appointment on Friday.

Until then.... stay home, stay safe.

You do not want this. Even a “mild” case means complete separation from your family and worry that you might have gotten someone else sick.

Someone who might not be as lucky as you.

Throughout this page and others, we will be posting haiku submitted to the Montview Neighborhood Listserv.

|

Trapped. Mind overrun.

Ghosts of the past haunting me. Where is the way through? -Jonathan Brody |

|

Essential workers

Send light and love to nurses Being home sounds nice -Michele Goulet |

|

not for Halloween

the masses amassing masks serious business -Lola Reid |

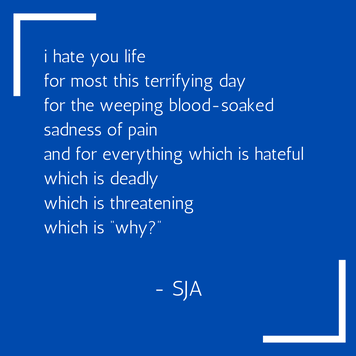

SJA

3/31/2020

(after e.e. cummings)

i hate you life

for most this terrifying day

for the weeping blood-soaked sadness of pain

and for everything which is hateful

which is deadly

which is threatening

which is “why?”

i who have died am still dead today

and this is mankind’s funeral.

this is the hollow notes of angst and arrows and suffering

and of the evil governing insanely trump.

how can gasping, crying, grasping, shouting

any human--

left here by invisible parents--

believe in true salvation?

now the breath of my lungs stops breathing and

now the ache of my heart has killed me.

(after e.e. cummings)

i hate you life

for most this terrifying day

for the weeping blood-soaked sadness of pain

and for everything which is hateful

which is deadly

which is threatening

which is “why?”

i who have died am still dead today

and this is mankind’s funeral.

this is the hollow notes of angst and arrows and suffering

and of the evil governing insanely trump.

how can gasping, crying, grasping, shouting

any human--

left here by invisible parents--

believe in true salvation?

now the breath of my lungs stops breathing and

now the ache of my heart has killed me.

Marisa Labozzetta

In the film version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story, “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” the 1922 tale of a man who is born old, ages in reverse, and dies in infancy, has been thrust into modern times and given a new ending that takes place in August of 2005, when hurricane Katrina raged in New Orleans.

The final scene depicts the dying heroine lying in a New Orleans hospital bed relating Benjamin’s and her story to her attentive daughter who learns for the first time that she is also Benjamin’s daughter. But from the hospital window the viewer sees that what is happening outside foretells a larger more ominous story that the characters are unaware of. Daylight turns into eerie darkness; a storm is brewing, one that we know will rage and destroy much of the city including many within the hospital walls.

As my mother spent her last days in a serene blue room at the Hospice of the Fisher Home in Amherst in early March of this year, I could not help but feel we were, in some odd way, reenacting that final movie scene. While I tended to my mother, each morning my ears listened to New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo give his dire briefing that reverberated on cable news stations throughout the day. Outside the hospice walls, the coved-19 virus, already having wrecked havoc on China, still fiercely afflicting Italy, and now pummeling the Big Apple, gathered force.

No sooner had my husband and I transferred my mother from her former residence in the Gardens at Rockridge Retirement Community, did the doors close to all visitors, including family. Before long, so too did the Fisher Home exclude visitors, with the exception of immediate family members whose temperatures were taken before entering. Subsequently masks were required to be worn. Each day brought new guidelines everywhere. In accordance with the order to shelter in place, the staff at the Fisher Home shrank to a skeleton crew. Gone were most of the cheery sympathetic co-workers who were now ordered to work from home. Those that remained searched the kitchen for food to prepare because gone too were the volunteers who, on a daily basis, brought delicious meals to staff, residents, and guests, and filled the refreshment bar with sumptuous cakes and cookies.

Since I had literally taken up residence in the home to see my mother through her final moments, I was, on occasion, restricted to my mother’s room and had to be served my morning coffee and afternoon tea. My daily hour walk around the peripheries of a bustling university turned into a stroll through a ghost town due to the never-ending spring vacation from which students were told not to return, the halting of daily work traffic, and the shuttering of local restaurants that advertised limited hours of takeout only.

I had already decided not to hold a wake so as not to put friends and out-of-town family in the difficult position of having to decide whether or not to attend. I deliberated on the specifics of a funeral—maybe just for locals since it would be outdoors. But within a day of having made my decision, wakes were added to the list of social gatherings that had at first been limited to 50 persons and were now reduced to ten. “Don’t delay,” the funeral director advised on selecting a burial date. “Things are changing every day.” If I assured the limited number and social distancing, the diocese would allow a Mass to be held, although daily Masses had been halted. We were afforded a viewing for seven of us. The Mass, ten in attendance, was quiet (the vocalist had a cold and did not dare enter Our Lady of the Hills church); there were no eulogies. At the Spring Grove gravesite, we learned there would be no more Masses or calling hours with any number of attendees. In some places around the globe funerals would come be witnessed by one family member from a car, and in other places there would be no funerals at all. Each day brought a new aspect of learning to live with this disease.

Many from my large Italian family lamented the fact they could not pay their last respects to their beloved relative, could not be there to reminisce about her life and their part in it. At first, my son, living in Florida, refused to believe he would miss his own grandmother’s funeral. “You were the last to speak on the phone with her,” I said to ease his sorrow.

There was no large gathering afterwards, no place to go, just a simple and brief put-together meal at my home. Because it was a cold rainy day and we could not be in the yard as planned, we made this exception. My husband, two daughters, son-in-law, and two grandsons were all careful to maintain space between us. No hugs of comfort. Over five weeks have since passed, and they have not returned to my house nor my husband and I to theirs. And yet we were the lucky ones, grateful to have been at my dying mother’s side, able to provide closure and a proper sendoff, unlike so many others who remain in limbo awaiting an interment of any sort.

We all wait. For the virus that continues to surge in Massachusetts and other places to abate. For orders on how and when to proceed outdoors, and to resume our working schedules. For life to return to a new normal.

The final scene depicts the dying heroine lying in a New Orleans hospital bed relating Benjamin’s and her story to her attentive daughter who learns for the first time that she is also Benjamin’s daughter. But from the hospital window the viewer sees that what is happening outside foretells a larger more ominous story that the characters are unaware of. Daylight turns into eerie darkness; a storm is brewing, one that we know will rage and destroy much of the city including many within the hospital walls.

As my mother spent her last days in a serene blue room at the Hospice of the Fisher Home in Amherst in early March of this year, I could not help but feel we were, in some odd way, reenacting that final movie scene. While I tended to my mother, each morning my ears listened to New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo give his dire briefing that reverberated on cable news stations throughout the day. Outside the hospice walls, the coved-19 virus, already having wrecked havoc on China, still fiercely afflicting Italy, and now pummeling the Big Apple, gathered force.

No sooner had my husband and I transferred my mother from her former residence in the Gardens at Rockridge Retirement Community, did the doors close to all visitors, including family. Before long, so too did the Fisher Home exclude visitors, with the exception of immediate family members whose temperatures were taken before entering. Subsequently masks were required to be worn. Each day brought new guidelines everywhere. In accordance with the order to shelter in place, the staff at the Fisher Home shrank to a skeleton crew. Gone were most of the cheery sympathetic co-workers who were now ordered to work from home. Those that remained searched the kitchen for food to prepare because gone too were the volunteers who, on a daily basis, brought delicious meals to staff, residents, and guests, and filled the refreshment bar with sumptuous cakes and cookies.

Since I had literally taken up residence in the home to see my mother through her final moments, I was, on occasion, restricted to my mother’s room and had to be served my morning coffee and afternoon tea. My daily hour walk around the peripheries of a bustling university turned into a stroll through a ghost town due to the never-ending spring vacation from which students were told not to return, the halting of daily work traffic, and the shuttering of local restaurants that advertised limited hours of takeout only.

I had already decided not to hold a wake so as not to put friends and out-of-town family in the difficult position of having to decide whether or not to attend. I deliberated on the specifics of a funeral—maybe just for locals since it would be outdoors. But within a day of having made my decision, wakes were added to the list of social gatherings that had at first been limited to 50 persons and were now reduced to ten. “Don’t delay,” the funeral director advised on selecting a burial date. “Things are changing every day.” If I assured the limited number and social distancing, the diocese would allow a Mass to be held, although daily Masses had been halted. We were afforded a viewing for seven of us. The Mass, ten in attendance, was quiet (the vocalist had a cold and did not dare enter Our Lady of the Hills church); there were no eulogies. At the Spring Grove gravesite, we learned there would be no more Masses or calling hours with any number of attendees. In some places around the globe funerals would come be witnessed by one family member from a car, and in other places there would be no funerals at all. Each day brought a new aspect of learning to live with this disease.

Many from my large Italian family lamented the fact they could not pay their last respects to their beloved relative, could not be there to reminisce about her life and their part in it. At first, my son, living in Florida, refused to believe he would miss his own grandmother’s funeral. “You were the last to speak on the phone with her,” I said to ease his sorrow.

There was no large gathering afterwards, no place to go, just a simple and brief put-together meal at my home. Because it was a cold rainy day and we could not be in the yard as planned, we made this exception. My husband, two daughters, son-in-law, and two grandsons were all careful to maintain space between us. No hugs of comfort. Over five weeks have since passed, and they have not returned to my house nor my husband and I to theirs. And yet we were the lucky ones, grateful to have been at my dying mother’s side, able to provide closure and a proper sendoff, unlike so many others who remain in limbo awaiting an interment of any sort.

We all wait. For the virus that continues to surge in Massachusetts and other places to abate. For orders on how and when to proceed outdoors, and to resume our working schedules. For life to return to a new normal.