Ancient Traditions

|

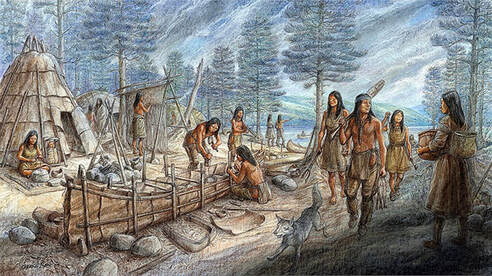

Native Lifeways

Eastern Algonkian (Wôbanaki) lifeways and technology before European contact. This scene shows a small seasonal encampment with both conical and domed wigwams, and people engaged in a range of activities, including basket-making, weaving mats, building a canoe, fishing, etc. Illustration by Francis Back for the website Raid on Deerfield: The Many Stories of 1704. Courtesy of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA. For more information, see: http://1704.deerfield.history.museum/groups/lifeways.do?title=Wobanakiak

|

|

Bluestem Grassy Area

Before European contact, many of the sandy outwash plains, and former deltas of the glacial lake contained a mix of little bluestem and big bluestem grasses. Open, grassy areas, mixed with pitch pine, scrub oak, little bush blueberry and other fire-tolerant species, were also created by Indigenous people through intentional burning. Such habitats, which are now exceedingly uncommon, supported an unusual assemblage of plant and animal species. Photo by Laurie Sanders, taken at Spring Grove Cemetery, near Broad Brook in Northampton.

|

Locating Nonotuck

|

Mohegan Environs Map

This map illustrates the Indigenous territory that now constitutes southern New England, highlighting the tribal communities located along the Kwinitekw (Connecticut River) while also noting some of the other surrounding tribal nations. Map created by Jenny Davis and Lisa Brooks, using ArcGIS 9.2, courtesy of Harvard University. From Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: the Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (University of Minnesota Press 2008). For more information, see:

https://lbrooks.people.amherst.edu/thecommonpot/map7.html |

|

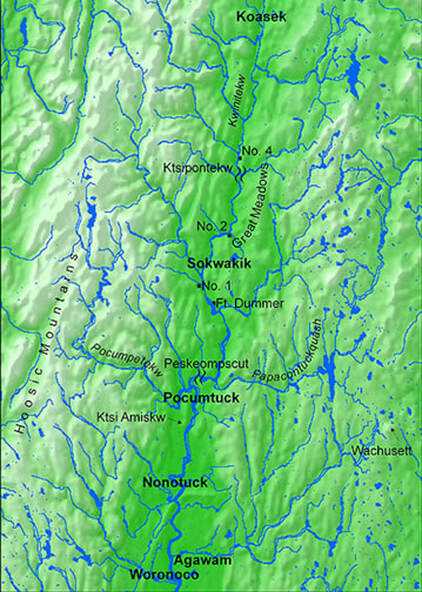

Kwinitekw Map

This map illustrates the central part of the river Kwinitekw from Koasek (in present-day Vermont) to Ktsipontekw, the “great falls” in Sokoki territory, to Peskeompscut, the “great falls” in Pocumtuck territory, with Native wôlhanak (“hollowed out places,” or intervales) highlighted. This map also notes the locations of four 18th century colonial settler forts (Fort Dummer, Fort No. 1, Fort No. 2, and Fort No. 4) that were temporarily situated within this Native space. Map created by Jenny Davis and Lisa Brooks, using ArcGIS 9.2, courtesy of Harvard University. From Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: the Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (University of Minnesota Press 2008). For more information, see: https://lbrooks.people.amherst.edu/thecommonpot/map3.html

|

Maize Horticulture

|

Native Cornfield

This scene shows two Native historical interpreters from the Wampanoag Indigenous Program working in a Native corn field at the re-created 17th century-style Wampanoag homesite on the Eel River, at Plimoth Patuxet Museum. The site displays bark-covered wetus (wigwams), dugout canoes, fishing nets, cooking fires, and other Indigenous living history activities. Photo by Margaret Bruchac.

|

|

Native Flint Corn

Two varieties of Indigenous 8-row flint corn, one yellow and one white. These heritage varieties, which were common across the 17th century Northeast, differ from modern-day hybrids of both sweet corn and flint corn that typically have 14-16 rows per ear. Photo by Margaret Bruchac.

|

Trading in Furs

|

Beaver

In North America, fur-trading between Indigenous people and Europeans began in the late 16th century, and of all the fur-bearing animals, beaver pelts were the most desired. The soft downy under-fur was excellent for felting to make hats, which were then the fashion-of-the-day. The pressure on American beavers coincided with the collapse of the Eurasian beaver population, which had been seriously reduced from intense overhunting. By the mid-1600s, the beaver population in the Connecticut River Valley had been decimated, and competition between Native hunters and English colonists also threatened beaver colonies in the Berkshires and to the north. By the mid-20th century, beaver populations rebounded, here and elsewhere across the Northeast. Photo by Laurie Sanders

|

|

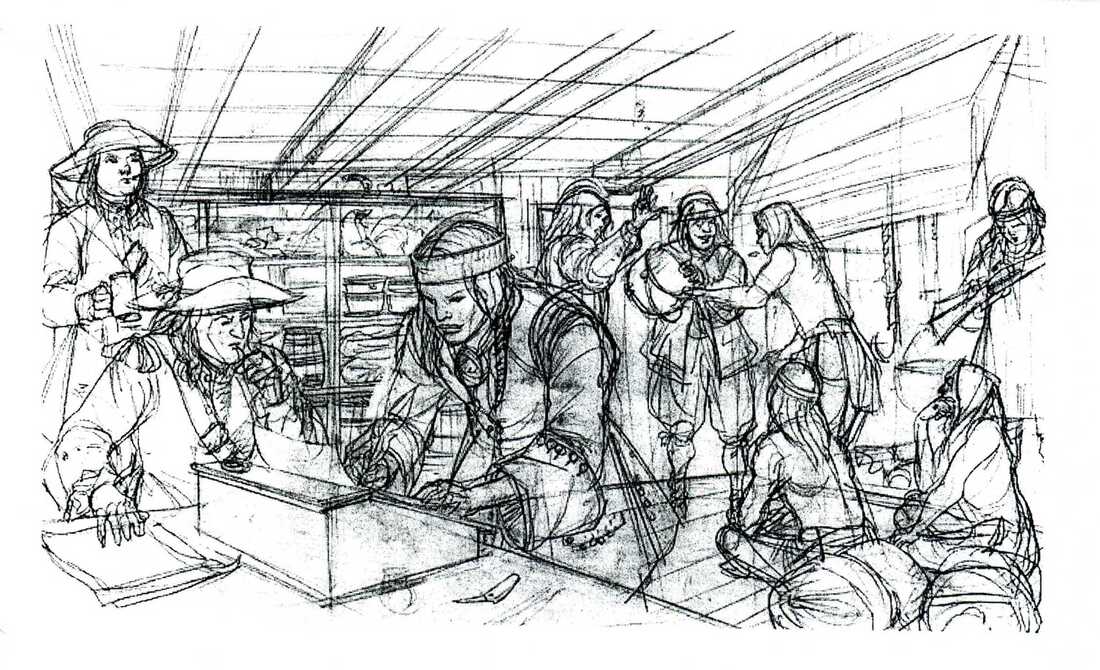

Mashalisk Trading with John Pynchon, 17th Century

From the 1630s to the 1660s, large numbers of Native people traded with merchants and land brokers William and John Pynchon, exchanging furs, corn, and wampum for English goods. Here, the Pocumtuck Sunksqua (female sachem) Mashalisk is shown making a transaction with John Pynchon in the 1660s. Illustration by Francis Back for the website Raid on Deerfield: The Many Stories of 1704. Courtesy of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA. For more information, see: http://1704.deerfield.history.museum/groups/lifeways.do?title=Wobanakiak

|

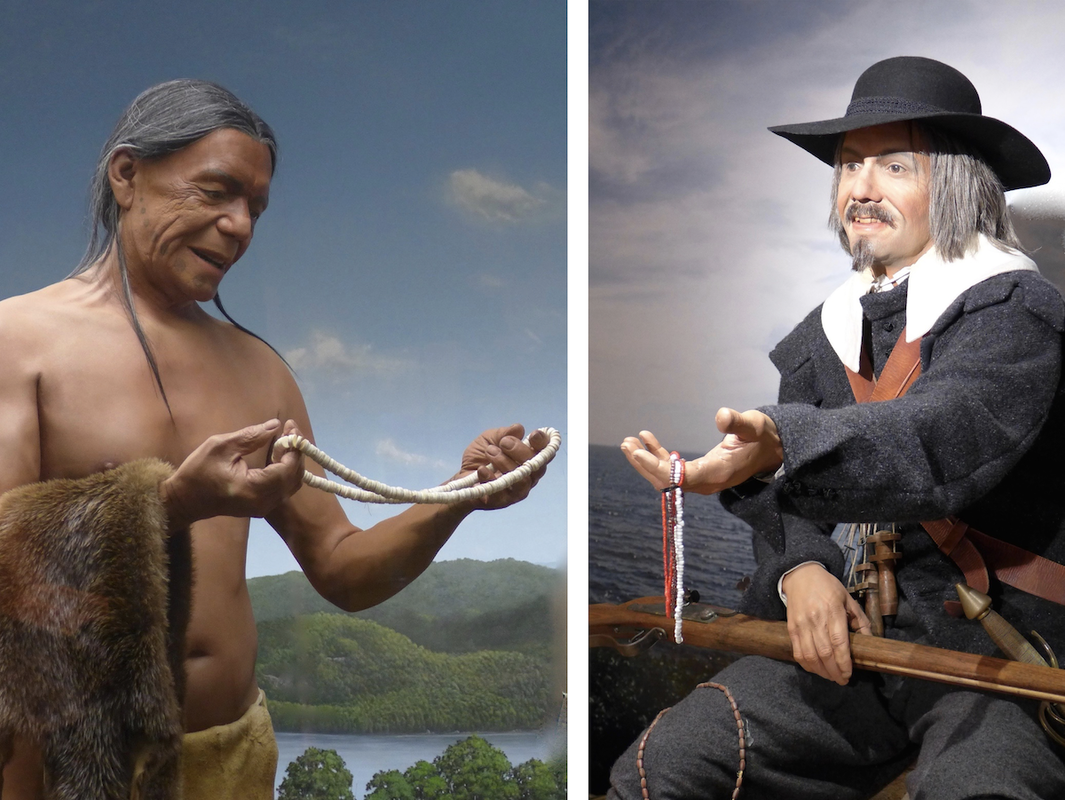

Trading with Wampum

|

Wampum Beads 1

Wampum beads carved from whelk and quahog shells were widely utilized by Northeastern Native people for adornment, exchange, ritual and diplomatic purposes. During the mid-1600s, English and Dutch colonists also used wampum as substitute currency, calculating values in fathoms (6 foot long strands, roughly 240 beads, worth about 5 shillings) and hands (4 inch strings, roughly 24 beads, worth about 6 pence), rather than in pounds, shillings, and pence. Photo by Margaret Bruchac.

|

|

Wampum Beads 2

Close-up image of 17th century wampum beads. White beads were traditionally carved from the central spiral columns of young whelk (Busycon canaliculatum and Busycon carica); purple beads were carved from the hinges of mature hard-shell clams or quahogs (Mercenaria mercenaria or Venus mercenaria). Photo by Margaret Bruchac.

|

King Philip's War

|

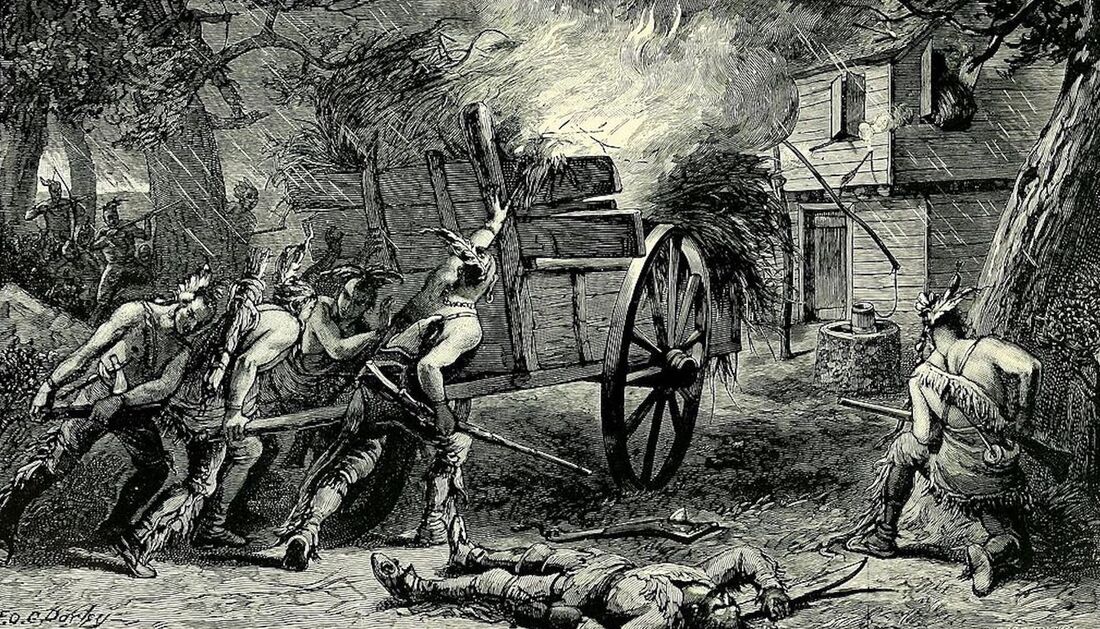

Burning of Brookfield

During King Philip’s War, also known as Metacom’s Rebellion (1675-1676), Native combatants reacted to English incursions by attacking 52 English towns in Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Rhode Island, and Connecticut colonies. In July 1675, Nonotuck men joined forces with Wampanoag and Nipmuc men in one of the first attacks, on Sargent Ayre’s Inn in the town of Brookfield, MA, in Quaboag territory. Illustration by F.O.C. Dorley in Josiah H. Temple, History of North Brookfield, Massachusetts. (Town of North Brookfield 1887), p. 84. For more information, see: https://archive.org/details/historyofnorthbr00temp/page/n5/mode/2up

|

Schaghticoke

|

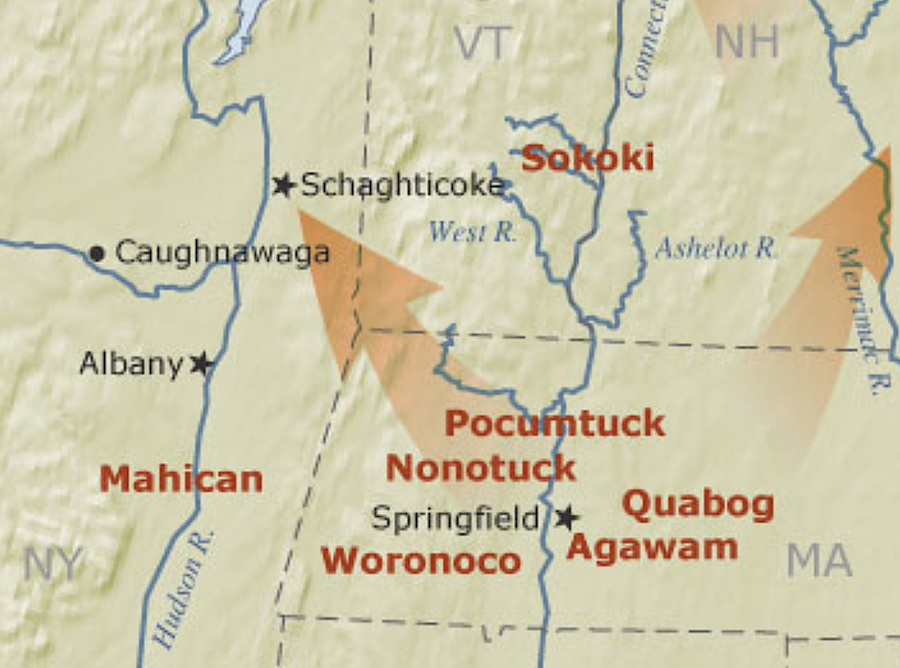

Schaghticoke

In the years after King Philip’s War (1676-1676), thousands of Native people were forced to relocate from southern and central New England to northern and western locales. Hundreds of Agawam, Nonotuck, Pocumtuck, Sokoki, and Woronoco people moved to the new refugee village in Mahican territory at Schaghticoke, where they lived under the protection of New York Colony until the 1740s, when the village was abandoned. Detail from map created for the website Raid on Deerfield: The Many Stories of 1704. Courtesy of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA. For more information, see: http://1704.deerfield.history.museum/groups/lifeways.do?title=Wobanakiak

|

Violent Encounters and Harsh "Jutstice"

|

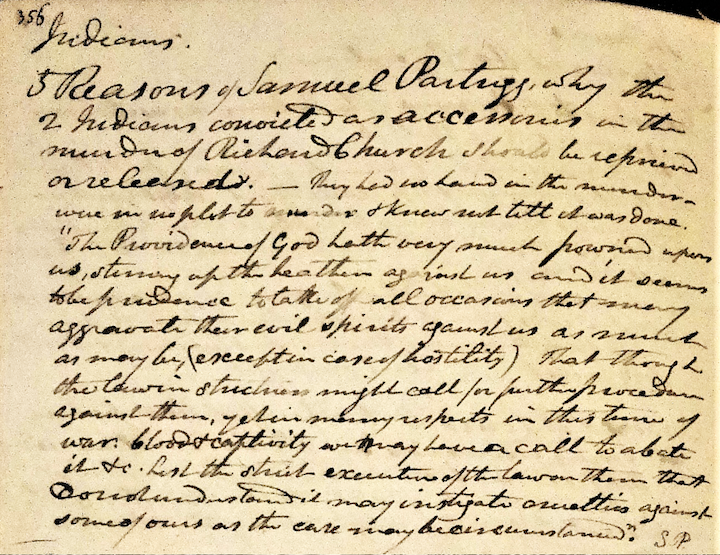

Samuel Partridge 1696

This excerpt, drawn from the October 1696 Records of the General Court of Northampton, details the testimony of Samuel Partridge (here spelled Partrigg) concerning two Nonotuck men charged with the murder of Richard Church, a Hatfield colonial settler found hunting in Nonotuck territory. Partridge argued that Wenepuck and Pemequansett should be released, since they “had no hand in the murder – were in no plot to murder & knew not till it was done.” Transcription by Sylvester Judd, in his Massachusetts Series, Volume 1, Part 2, p. 356, manuscript housed at Forbes Library, Northampton, MA. Photo by Peter Thomas.

|

Historical Relocations: A Matter of Life or Death

|

Diaspora Map

From the late 1600s and throughout the 1700s, thousands of Native people were forced to relocate from southern and central New England to northern and western locales. This map illustrates the flows of that diaspora as Native families folded into other Native communities, sometimes for only a few years, sometimes for generations, to escape colonial conflicts. These movements created a great deal of confusion in tribal identities, especially in Catholic Missions where families from multiple tribal communities banded together under the protection of the French. This illustration was inspired by an earlier map by Evan Haefeli and Kevin Sweeney for Captors and Captives: The 1704 French and Indian Raid on Deerfield (University of Massachusetts Press 2003), and updated for the website Raid on Deerfield: The Many Stories of 1704. From the website Raid on Deerfield: The Many Stories of 1704. Courtesy of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA. For more information, see: http://1704.deerfield.history.museum/groups/lifeways.do?title=Wobanakiak

|

Historical Persistence: Hiding in Plain Sight

|

Native Baskets at Historic Northampton

Native-made ash-splint baskets were often marked with various symbols, made with paint and potato stamps, that were more than just decorative. On some baskets, these designs communicated personal and tribal identities. Although the maker of this particular basket is unknown, it has designs that were commonly used by Nipmuc artisans. Note the domed symbols in red and black across the top and down along the edges, and the stockade design on the body of the basket. Collection of Historic Northampton. Photo by William Holloway. For more information on regional Native basketry designs, see Tara Prindle, “Nipmuc Splint Basketry,” on NativeTech: http://www.nativetech.org/weave/nipmucbask/

|

|

Traveling Nipmuc Basketmakers c. 1848

Two Nipmuc women and a child peddling ash-splint baskets in Natick, Massachusetts, c. 1848. Thousands of ash-splint baskets were made in the mid-19th century by itinerant Indigenous artisans for personal use and for sale to their non-Native neighbors. Throughout the 1800s, in many parts of rural Massachusetts, non-Native farmers would allow traveling groups of Native people to freely harvest standing ash trees to make baskets for trade and sale. Illustration from Sarah Sprague Jacobs, Nonantum and Natick (Boston, MA: Massachusetts Sabbath School Society 1853). For more information on itinerant Indigenous artisans, see Nan Wolverton, “A Precarious Living: Basket Making and Related Crafts Among New England Indians,” online at: https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/1409

|

Indian Doctors and Doctoresses

|

Indian Doctresses

During the 1700s and 1800s, Indigenous medicinal practitioners were commonly identified as “Indian Doctors” or “Indian Doctresses.” These titles were sometimes inscribed on their tombstones, as can be seen in the image on the left, marking the burial place of Rhoda Rhoades, a Mohican Indian Doctress, in Indian Hollow, MA. To bring the lives of these Native healers to the attention of the general public, Margaret Bruchac has long performed in historical garb as “Molly Geet, the Indian Doctress,” as shown on the right, at the living history site of Old Sturbridge Village Museum. Photos courtesy of Margaret Bruchac.

|

|

Williams Herbarium and Joe Pye

Although white doctors tended to view Indian Doctors as primitive, they nonetheless were keen to acquire Indigenous knowledge of plant medicines. The photo on the left shows an Herbarium compiled in the early 1800s by Dr. Stephen West Williams, who consulted with Abenaki Indian Doctor Louis Watso. This brown leather portfolio, which contains 411 specimens of Indigenous plants found growing wild around Deerfield, is housed at Memorial Libraries in Deerfield, MA. The photo on the right shows Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium purpureum), an Indigenous plant favored by Indian Doctors for treating fevers and respiratory ailments. Photos by Margaret Bruchac.

|

The Maminash Family

|

Native Home 19th Century

This life-size diorama portrays a Pequot home in the mid-1800s, typifying the ways in which Native people combined Indigenous and European material goods and lifeways. Note the distinctive Native elements in this woman’s garb – braided hair, beaded necklace, and deerskin moccasins. Also note the variety of ash-splint baskets used for storage. Diorama at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum. Photo by Margaret Bruchac.

|

|

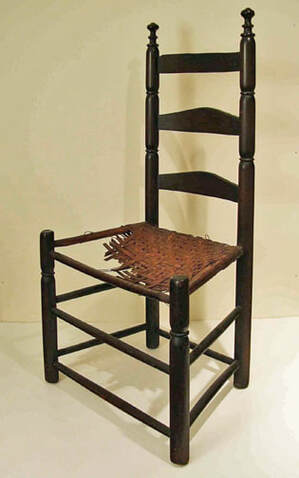

Sally Maminash’s Chair

This wooden ladder back side chair with woven ash splint seat was favored by Sally Maminash (Mohegan/Wangunk/Nonotuck, 1765-1853) when she lived with Sophia and Warham Clapp on South Street in Northampton. Family members recall her sitting in this chair by the fireside when reading from her Bible. The chair was likely made by a white craftsman, but the seat was likely woven by a Native artisan from locally harvested ash splints. Native itinerants routinely made and repaired both rush and ash-splint chair seats for non-Native households. The fact that this seat was broken and left unrepaired after Sally’s passing leads one to wonder if perhaps she was the weaver. Photo by Historic Northampton.

|

|

Maminash and Clapp Gravestones

Sally Maminash’s gravestone, situated in the family plot of Warham and Sophia Clapp in Northampton’s Bridge Street Cemetery, reads: “Sally Maminash. The last of the Indians here. A niece of Occum. A Christian. Died in the family of Warham & Sophia Clap. Jan. 3, 1853. Aged 88.” Photo by Margaret Bruchac. The inaccurate phrase – “last of the Indians” – was often used in the 1800s by non-Native historians who imagined that Native people were somehow doomed to disappear. For a critical discussion of this practice, see Jean M. O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England (University of Minnesota Press 2010).

|

Recovering the Past

|

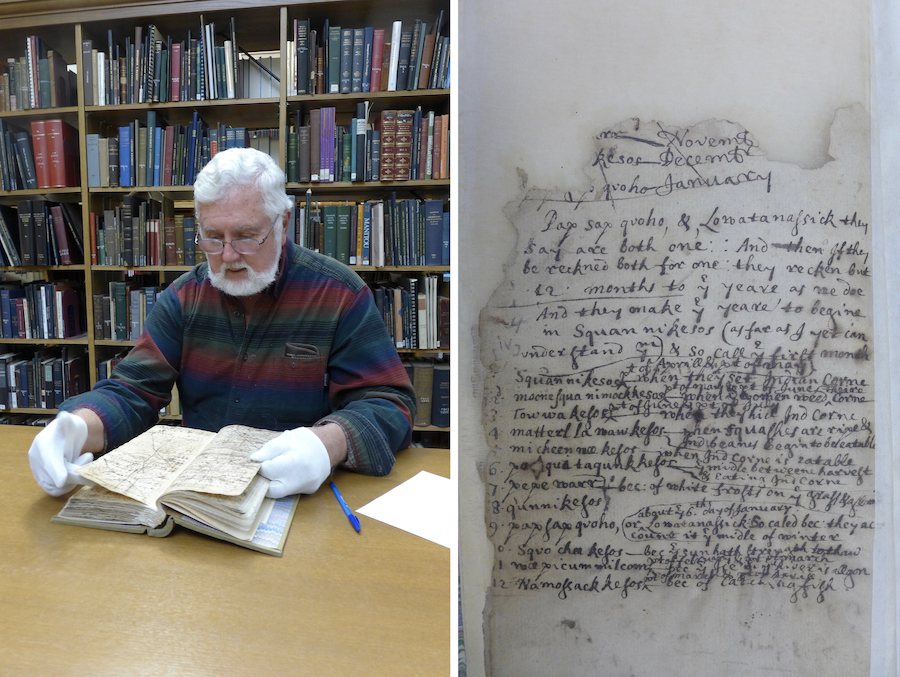

Peter Thomas and Pynchon Accounts

Peter Thomas, Archaeologist and Historic Preservation Specialist, is shown examining William Pynchon & John Pynchon’s Account Book from the 1640s – 1660s at Forbes Library in Northampton. Thomas has been methodically revisiting and transcribing 17th and 18th century manuscripts from the Pynchons and others that include documentation of colonial encounters with Native people in and around Northampton. Photo by Margaret Bruchac.

|

|

Lisa Brooks and Laurie Sanders

Lisa Brooks, Professor of English and American Studies at Amherst College, and Laurie Sanders, Co-director of Historic Northampton, are standing in a small grove of black birch trees, at the top of the slope near the meadows along the Mill River, on the former Northampton State Hospital grounds. Large trees like the one pictured here were widespread in local forests before European contact. Photo by Margaret Bruchac, taken behind Hospital Hill in Northampton, 2019.

|

|

Margaret Bruchac with Steatite Pot

Margaret Bruchac, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, with Native steatite cooking pot from an unidentified site in Quaboag territory in Brookfield, MA. This pot, one of many collected by Amherst College, is now housed in the Historic Northampton collection. Photo courtesy of Margaret Bruchac.

|