Dressmakers on Northampton's Main Street in the Nineteenth-Century

by Lynne Zacek Bassett

Women have always worked outside the home to earn cash. The textile trades especially have offered opportunities for women who needed to support themselves or their families. Work opportunities, which had been quite broad previously, narrowed for women in the 19th century, due to the ideals of the Romantic Era, which promoted idealized concepts of medieval male chivalry and female angelic docility. However, the needle trades remained open for women, and Northampton’s Main Street was lined with dressmakers and milliners throughout the 19th century.

The Civil War from 1861 to 1865 led to what the Hampshire Gazette in 1891 uncharitably called “an excess of women.” It’s now estimated that 750,000 men were killed in the Civil War. Tens of thousands more were wounded, or broken in their physical or mental health by prisoner-of-war experiences, and could no longer support their families. Women were forced to enter or stay in the workforce in unprecedented numbers.

Post-Civil-War America enjoyed a robust economy based on manufacturing. Extravagant displays of wealth—what economist Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption” in his 1899 book, The Theory of the Leisure Class—became the fashion. The prosperity of the middle and upper classes, along with technological developments in sewing, weaving, lace making, and pattern drafting, created a fashion for elaborately embellished women’s garments. The complexity of fashionable drapery and fit in dresses proved too daunting for the skills of most home sewers. Thus, the late Victorian era was a boom period for professional dressmakers and well-timed for the thousands of women who had to make their own way following the losses of the Civil War.

Locally, the dressmaking trade reached its zenith in 1900, when the Northampton Directory listed 73 dressmakers, or one dressmaker for every 258 Northampton residents. However, many other women worked as dressmakers without claiming the title, as indicated by the Daily Hampshire Gazette. In an article dated June 12, 1891 titled, “Among the Dressmakers,” the Gazette noted that “Few cities have so great an excess of women over men as Northampton,” adding that “Northampton’s over 2000 excess seems to impress itself on us.” They asked, “What does this excess do?” They claimed 97 were dressmakers (24 more than indicated in the 1900 city directory, which listed more dressmakers than any other year). In all, the Hampshire Gazette reporter found as he was researching his article that “over 200 women…make a living by clothing and adorning the bodies of their sex, and there must be many more.” Of the 15 dressmakers interviewed for the article, eight were noted to be located on Main Street. Five stated that the students of Smith College were a very important segment of their clientele.

Few dressmakers labeled their creations. If a label exists, it can usually be found on the petersham, a ribbon belt inside the dress, which was fastened around the wearer’s waist to keep the bodice from shifting out of alignment with the skirt. It can be assumed that many other dresses in Historic Northampton’s collection were made by local dressmakers; however, without a label, that information is generally lost.

|

Miss L. J. Loud. Fashionable Dress Maker,

NORTHAMPTON, Mass. Label inside dress 1978.92.2 |

Lucie Jerusha Loud’s labels describe her as a “Fashionable Dress Maker.” Perhaps her interest in style led her to use an inheritance from her father to travel in Europe for two years. When she returned from Europe in 1896, she was again listed in the city directories as a dressmaker. Certainly, she brought home knowledge of the latest European modes. She continued to work as a dressmaker until about 1909, when—perhaps recognizing the decreasing need for professional dressmakers—she turned her energies to running “The Anchorage,” a local landmark and highly regarded rooming house on South Street. When she died at age 74 in 1930, having never married, she bequeathed more than $12,000 and stock in an oil company to two cousins, evidence of her success as a businesswoman.

|

“I say dressmakers ought to get as good pay as a laboring man, from $1.50 to $4 a day. They don’t work any harder than we do, only theirs is more manual labor, and ours brain work.”

— Mrs. M. R. Lewis, Jr.,

“Among the Dressmakers,” Hampshire Gazette, June 12, 1891.

— Mrs. M. R. Lewis, Jr.,

“Among the Dressmakers,” Hampshire Gazette, June 12, 1891.

Dressmaking was one of the few careers allowed women that offered the potential to make a living wage, though seldom actual wealth. A dressmaker combined her business acumen with pattern drafting and sewing skills—but to be truly successful, she needed to be an artist. Her understanding of color, fabrics, and tasteful ornamentation brought customers to her door.

Mrs. Lewis (quoted above) was having a tough time of it. While most of the other dressmakers interviewed by the Hampshire Gazette reporter said that they had all the work that they could handle and more, Mrs. Lewis of 219 Main Street said that in the three years that she had done business in Northampton, she had “found it very difficult to pay our way.” Lizzie Violet, another Northampton dressmaker, was similarly short of clients. She and her husband had come to Northampton from Fall River four months earlier, and her husband had recently suffered an accident that caused him to go deaf. Mrs. Violet said that she had “not much work yet, and God knows I need it.” She felt her shop was located too far up Main Street and wished that she could afford the rent in a busier part of downtown.

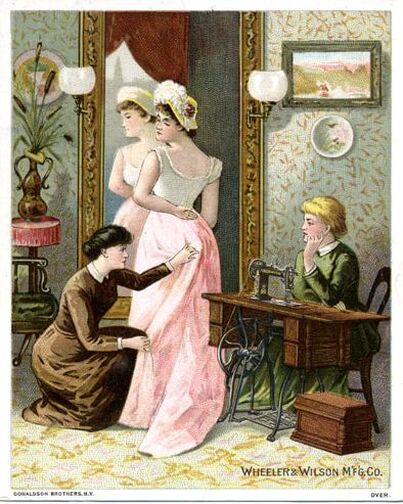

Women in the clothing trades had to work very hard to make a living, even if they had a large clientele. This illustration from a c. 1880 newspaper has the following caption: “This picture tells its own sad tale. The ball-dress, destined to grace the form of some wealthy belle, must be completed that the girl who broiders it may win bread. Dawn is coming in at the casement to find the weary and worn seamstress still at the work that kills.” Mrs. E. P. Knight noted in her interview that she had “broken down under the heavy pressure of business,” and so had cut back on her workload, finding “it agrees with me better.” She was apparently in the happy position of not having to earn an income to support an entire household.

Seamstresses—those who could only construct simple items like shirts and trousers, or who sewed the seams for dressmakers, but did not know how to “cut” (meaning to draft a pattern)—generally received only starvation wages. The newspaper gave the wages earned by the Northampton dressmakers: “Their prices and wages vary, wages being about $1 a day without board. There is a large class of women who ‘go out’ sewing, and they get from $1 to $1.50 per day…. They unite the duties of the seamstress with those of the cutter and fitter.” Those wages are far better than urban seamstresses working in sweatshops, who typically earned about 25 cents a day, but $1.50 was nevertheless a low daily wage for such skilled work, and it seems even that minimal amount was not always met.

Many of the Northampton dressmakers interviewed by the Hampshire Gazette stated that they employed seamstresses and dressmakers to help them—anywhere from one helper, with whom Madame Fernstrom at 155 Main Street declared she worked with regularly into the night hours, to Mrs. Twiss, who employed as many as 12 helpers in her busy season. Mary Dickinson stated that she employed a “large corps of assistants” to keep up with her orders.

Only two of the dressmakers interviewed by the Gazette used the prefix of “Madame,” and neither was actually French. It was a common affectation suggesting an association with Paris, the fashion center of the Western world. Madame Lloyd was reported to have been found “just up to her eyes in business” in her salon on Court Street. She told the reporter, “To my perfect fitting, I owe my success and popularity.” Indeed, a perfect fit was a sign of prestige and a degree of wealth. As Mrs. L. C. Knapp stated in her interview, “You cannot make a $5 suit and have it fit. People who know a good fit know that they have to pay for it.”

The acknowledged leader of Hampshire County fashionable dressmaking was Mary Clark Ferry. While family stories rather inflate her reputation, stating that her clientele included Lily Langtry and Sarah Bernhardt (neither is possible), the memory that she sewed for wealthy clients from New York certainly is likely accurate.

Photographs of Mary Ferry reveal her unmistakable air of self-confidence and love of fashion. As a working wife and mother, Ferry was an unusual woman for her time. It seems that she worked for the satisfaction of it. In fact, Mary was her husband’s employer, as he was the bookkeeper for her dressmaking business.

Her fashions were desired by the leading ladies of Hampshire County. As the daughter of George A. Burr, a wealthy and prominent Northampton manufacturer, Fannie Burr could have had her wedding dress made by a famous New York or Boston couturier. It is evidence of the sophisticated fashions available from local dressmakers that Fannie chose Mary Ferry. A contemporary account of the “large and fashionable wedding” reveals that the ladies in attendance pronounced the dress “just splendid,” an advertisement of the best kind for the skills of Mrs. Ferry. The dress features openwork on the sleeves covered with strings of pearls, and a picot edge of hand-stitched pearls along the edge of the bodice and skirt drapery. (The dress is in the collection of Historic Northampton, accession number 66.193a-b. The skirt was altered probably in the 1880s to make the drapery asymmetrical.)

Mary Ferry began her dressmaking career as the sole proprietress of a shop, but started working in a successful partnership with Mary Dickinson around 1868. Together, they dressed Northampton women from “the best families” (to quote Mary Dickinson in the Gazette article), as well as students from Smith College. They employed a group of seamstresses, and several later dressmakers were proud to claim apprenticeship with them. In the reminiscence, Around a Village Green (1939), Mary Adèle Allen described dresses worn by women from elite Amherst families: “These dresses were made by the famous dressmakers of Northampton, Mmes. Ferry and Dickinson, whom many in Amherst patronized. It may be of interest to know that the standard price for making a dress was fifty dollars, aside from linings and furnishings. The bill for extras was also headed by the item: ‘Sewing silk, two dollars.’” The tasteful elegance of their designs can certainly be seen in this dress, with its magnificent draping and a fit that was undoubtedly perfect. The quality of their work can be seen also in the perfect finishing of the seams of the bodice interior.

Ferry & Dickinson’s salon was on Main Street, over Lincoln and Southwick’s Store. Sometime before 1876, they moved to 102 Main, over Copeland’s Bazar, which called itself “a Fashion Emporium.” Copeland’s sold fashionable accessories, and silks, wools, and cotton yard goods, as well as fans, silk flowers, and hosiery. The proximity of two such establishments was common, and provided stylish and convenient services for all well-dressed women and girls.

The Ferry and Dickinson partnership flourished until Mary Ferry’s sudden death from a stroke in 1881. Her obituary in the Hampshire Gazette noted her popularity in the community, praising her “unusual energy and force of character…[and] her lovable and generous disposition. She was a universal favorite with all our people.” Such a personality would have been another important quality for a self-employed dressmaker.

After Mary Ferry’s death, Mary Dickinson advertised her business as a “Fashionable Establishment…with shipments regularly received from New York City.” She remained at the location over Copeland’s Bazar until 1894. By 1897, she was no longer listed in the city directories. Interestingly, unlike Mary Ferry, who had an able husband with a useful career, Mary Dickinson appears to have needed to work to support herself and her family. She may have been estranged from her husband, as she had not used his name since the ’70s, and her 1899 will charged her two sons with his continued care.

As previously mentioned, Mary Ferry’s husband, Lemuel, was the bookkeeper for the Ferry & Dickinson dressmaking firm. One year after Mary’s death, he married another dressmaker, Harriet A. Phelps, who likely was one of the dressmakers employed by Ferry & Dickinson. Harriet, known as “Hattie,” established her own dressmaking shop on Main Street. She is seen at the upper right in this photograph. Standing in the center is dressmaker Mabelle Forrister Stearns, who married jewelry store clerk Edward John Gare in 1892.

Although Mabelle made her wedding dress in a practical shade of rusty brown so that she could continue to wear it as her best dress, it was far from ordinary. The large leg-o’-mutton sleeves were the height of fashion in the early 1890s and the ribbon fringe on the bodice was an elegant and imaginative touch. It was unusual for women to continue to work after marriage, but Mabelle worked for Hattie Ferry even after she married E. J. Gare. She left the dressmaking shop after her first child was born in 1893.

The development of separate blouses, jackets, and skirts in the 1890s, followed by looser fashions in the early 20th century—especially after World War I—spelled the demise of a robust custom dressmaking trade. A wide variety of off-the-rack clothing for women became available for the first time, and simpler styles allowed more home sewers to dress themselves. The numbers of dressmakers listed in the Northampton city directories declined significantly in the early 20th century, as jobs in a wider variety of professions opened up for women.

Two-piece silk dress, 1881, made by Mary Ferry & Mary Dickinson, dressmakers in Northampton, Massachusetts.