Frederick Douglass's Visits to Northampton and Florence

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was born enslaved on Maryland’s eastern shore. He barely knew his mother and was not certain of the identity of his father. At age twenty, in 1838, he escaped slavery and arrived in New York City, where he was assisted in freedom and later mentored by David Ruggles, an African American activist.

Just a few years after Douglass’s 1838 escape from slavery, he became one of the abolition movement’s greatest orators on slavery and abolition, speaking to large and small audiences across the country, to both praise and violent attacks.

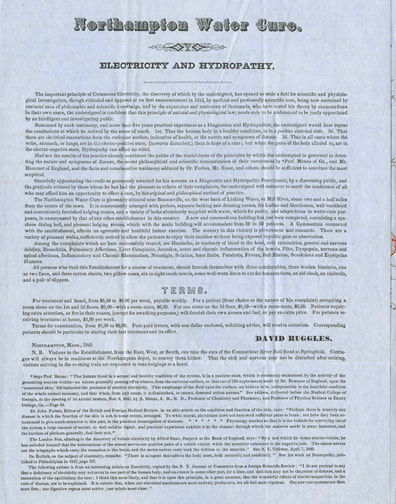

Frederick Douglass was most likely drawn to Northampton through David Ruggles and through the Northampton Association of Education and Industry founded in April 1842. The NAEI was an abolitionist and utopian community which aimed to manufacture silk on principles of equality and offer an alternative to the slave labor system. In November 1842, David Ruggles, in declining health, came to live at the Association, established a water cure, and continued his work as an anti-slavery activist. Ruggles's presence is believed to have attracted a significant African American population, both free-born and self-emancipated, to Florence.

Douglass visited Northampton and Florence at least six times (he never lived here), speaking about slavery and reconnecting with his friend and mentor David Ruggles. Newspaper articles, letters and personal reminiscences provide the following accounts of his visits.

Just a few years after Douglass’s 1838 escape from slavery, he became one of the abolition movement’s greatest orators on slavery and abolition, speaking to large and small audiences across the country, to both praise and violent attacks.

Frederick Douglass was most likely drawn to Northampton through David Ruggles and through the Northampton Association of Education and Industry founded in April 1842. The NAEI was an abolitionist and utopian community which aimed to manufacture silk on principles of equality and offer an alternative to the slave labor system. In November 1842, David Ruggles, in declining health, came to live at the Association, established a water cure, and continued his work as an anti-slavery activist. Ruggles's presence is believed to have attracted a significant African American population, both free-born and self-emancipated, to Florence.

Douglass visited Northampton and Florence at least six times (he never lived here), speaking about slavery and reconnecting with his friend and mentor David Ruggles. Newspaper articles, letters and personal reminiscences provide the following accounts of his visits.

|

April 27, 1844

Douglass’s first known visit to Northampton came on April 27, 1844. He spoke at the Northampton Association and at Northampton's Town Hall.

The famous Hutchinson Family Singers, with whom he occasionally toured, were performing in town and staying at the “Community.” While Community members and the singers were napping after a game of Bat Ball, an early form of baseball, they heard: "a rap at the door, and Frederick Douglass entered. Then came shaking hands, pulling, and hauling, loud talking, laughing, embracing, etc. We had not seen Fred in a year. He was in good health, full of anecdotes." The following morning Douglass spoke to members of the Community bringing many to “tears of real grief, tears for suffering humanity.“ As John W. Hutchinson later recalled, "On Sunday there was a meeting in the great dining room. Frederick Douglass, then so recently 'chattel personal,' who the following year went with us to Europe, to promulgate the gospel of freedom, was there, and spoke to the communists, as did one of the leaders, Mr. Hill, and others. We sang many of our songs." |

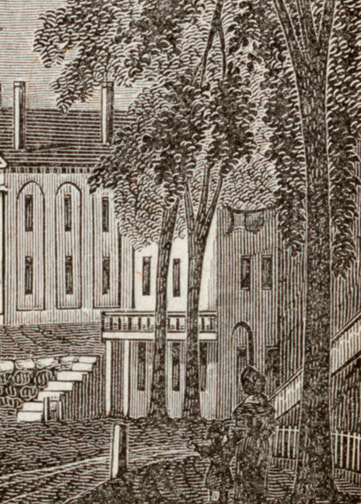

View of the Community boardinghouse and silk factory of the Northampton Association of Education & Industry

Stereoscopic Views of Florence, Knowlton Brothers Photographers |

|

On Sunday, April 28, 1844 Douglass gave a spirited talk at the town hall on Main Street in Northampton (then located where King Street meets Main Street) while the Hutchinson Family Singers performed anti-slavery songs. The local press was not favorable to Douglass. It was "announced on Sunday, by glaring handbills posted up, that Frederick Douglas [sic], a fugitive slave, would deliver an anti-slavery [address at] the Town Hall in the evening, and that the Hutchinsons would sing. A great number congregated, many more than could find seats, and a majority of them, undoubtedly, came to hear the singing.... Some were inclined to make disturbance; but we say, if people wish to hear such stuff, let them hear it. We regret, however, that the Hutchinsons should have suffered themselves to be used in such a manner." A rock thrown at Douglass during the speech became a treasured souvenir of Stetson family, who were Community members.

One audience member sent a letter to the anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, praising Douglass's “power, eloquence and force of argument." Wm. R. Small wrote, "A powerful and unflinching advocate in the cause of human rights is Douglass, as he proved himself to be last evening. The hall was crowded to overflowing, there being from five to six hundred present.... Friend Douglass spoke, with great earnestness, of the enormity of slavery. ‘Consider it as you may, the fact of your being a slave is enough to sicken the heart, and curdle the blood in your veins".... He then gave us part of his experience while in slavery ; a sad tale, truly, but intermingled with humorous bits of the fallacy of the slaveholder’s reasoning, if it can be so called." |

Detail showing Northampton's Town Hall from Central Part of Northampton, Mass., 1839.

Drawn by J.W. Barber & Engraved by S.E. Brown, Boston |

|

Portrait of Frederick Douglass, 1845

by Elisha Hammond. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution |

Frederick Douglass returned to the Community in the spring of 1845. Dolly Stetson wrote to her husband James on April 13, 1845, that most of the family have gone into town to listen to the “eloquent fugitive," and that he spoke at the community earlier in the day:

During this 1845 visit Douglass sat for a portrait by Community member Elisha Hammond. In a letter dated April 15, 1845, Dolly wrote, "I send this [letter] by Frederic [sic] Douglass ... Mr Hammond has been very successfull in his portrait if I am a judge." The pose is similar to the one on the frontispiece of his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave published two weeks after this visit. Hammond’s portrait is at the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C. |

|

After the publication of his slave narrative, it was no longer safe for Douglass to remain in the U.S. He sailed for Liverpool, England, on August 16, 1845, and returned in the spring of 1847. By November he had come to Springfield, Massachusetts, where he first met abolitionist John Brown. In November 1848, Douglass returned to Northampton. On November 18, 1848, he wrote to the anti-slavery newspaper North Star:

|

Advertisement for David Ruggles's Water Cure

Courtesy of the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections |

During his stay he gave controversial lectures in Florence and then in downtown Northampton on Thanksgiving. Perhaps the death of his friend and mentor David Ruggles in December of 1849 led to a gap in Douglass’s visits until the mid-1850s. The Hampshire Gazette gave brief, enthusiastic coverage of lectures given in town and in Florence in April of 1865 and January of 1866.

|

Cosmian Hall, Florence, Massachusetts

|

The Hampshire Gazette recorded another visit on November 17, 1874. Douglass gave two speeches at Cosmian Hall in Florence. “Fred Douglass delivered his lecture on John Brown at Cosmian Hall last Saturday evening to an audience that completely filled the hall. Even the aisles were furnished with chairs and occupied.” He spoke the following day: “Two car-loads of people from this town went to Florence, Sunday afternoon, to hear Frederick Douglass’ lecture on ‘Recollections of the Anti-Slavery Conflict.’”

Cosmian Hall was dedicated in March 1874 as the "Temple of Free Speech" for the Free Congregational Society in Florence. The society was founded in 1863 "on a platform of entire freedom of thought and speech." Membership was open "regardless of race, gender, or nationality." Cosmian Hall stood on the corner of Main and Meadow streets in Florence.

|

Douglass wrote his memories of Community days in Charles Sheffeld’s History of Florence, Massachusetts of 1894. “I visited Florence almost at its beginning,” he wrote, “The place and people struck me as the most democratic I had ever met.” He praised local residents who worked for emancipation but never reached his level of prominence:

|

It is hardly possible to point to a greater contrast than is presented by Florence now, and what it was fifty years ago. Then it was a wilderness. Now it blossoms like the rose. Though the outward form has changed, the early spirit of the Community has survived. The noble character of its men and women, and the spirit of its teachers, are still found in that locality, and one cannot visit there without seeing that George Benson, Samuel Hill, Mr. and Mrs. Hammond, Sophia Foorde, William Bassett, and Giles B. Stebbins, and the rest of them, have not lived in vain.

|

Douglass died February 20, 1895, in Washington, D.C. He is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

Research by the David Ruggles Center for History and Education www.davidrugglescenter.org