One object. many Stories.

Made on Main, and Made Again in Florence

How master furniture maker Sharon Mehrman recreated the Sarah Strong Chest

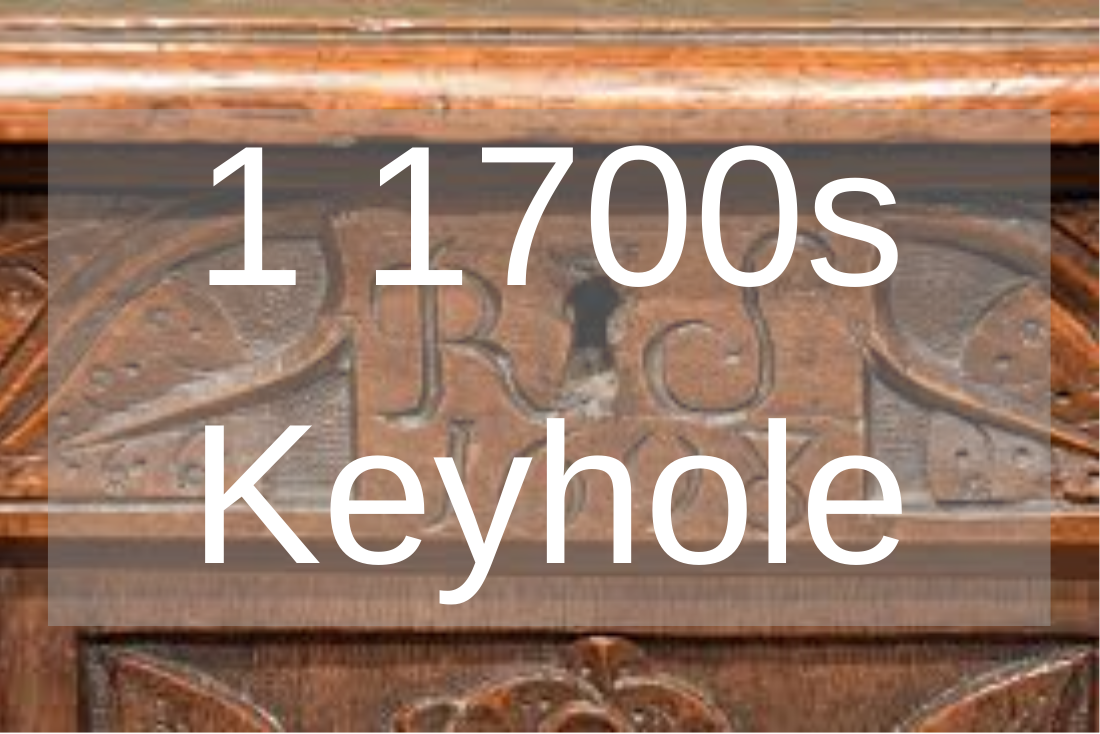

For master furniture maker Sharon Mehrman, making a 7/8 scale reproduction of Historic Northampton’s Sarah Strong Chest was a labor of love and forensics. Mehrman’s reproduction is in the hands-on learning section of the exhibit, Making it on Main Street. The original chest, made sometime between 1680-1740, is displayed in a glass cabinet in the exhibit. Visitors can touch and explore the reproduction chest to see the marks left by the tools used in marking and making the chest, and to learn about the chest’s construction.

The chest likely belonged to Sarah Strong, who lived on Main Street, where her father had a thriving business tanning hides to make leather. Strong was given this chest by her parents to outfit her for marriage. It held the most expensive items she needed to start housekeeping – linen sheets, towels, napkins, blankets, and perhaps some silver. Textiles were expensive because they were so time consuming to make. Women had few rights once married, so her name, carved on the chest, meant something. In the partriarchal system of the 17th and 18th century, a husband legally owned all his wife’s possessions, though it was culturally accepted that a woman owned the movable property (like a chest and linens) that she brought into the marriage. Sarah’s name protected her goods and ensured an inheritance for generations of daughters.

In an interview with the Daily Hampshire Gazette, Mehrman says making the reproduction chest was both fascinating and challenging – and she learned a lot along the way. She began by doing an in-depth study of the chest, of which there are only about 135 known to have survived. Of those, only six have a woman’s full name carved on them. These chests were typically monogrammed, so the fact that Sarah Strong’s full name is on it is a bold statement of ownership at the time when women did not legally own property. “The original chest is one of those pieces of furniture that is really special,” Mehrman said. “Making the reproduction married the two loves I have of history and woodworking, and I was really intrigued and excited about the insights into the original I gained by making the chest.”

Early American woodworking techniques are very different from modern ones, she said. Mehrman used many of the hand tools that the original craftsman did. On the original she saw plenty of evidence of tool marks: planes, chisels, scratch awls, dividers, etc., all of which help tell the story of how it was made. Her study and her work also demonstrated that the Strong chest was made by several people working on it at once – while Mehrman worked alone. “It took me a lot longer than it probably took them,” she said. “They weren’t fussy, they were making them fast,” she said. Even so, the chest was executed to a very high of skill, she said.

At every step, she said, she learned something new. “I wanted to reproduce the chest as closely as I could. The challenge was that every time I gained a new insight, I had to look deeper.” An example of that was her discovery about the front of the original chest. It has an unusual front, a type you don’t ordinarily see. I didn’t really understand this until I was working on the replica.” The joinery is different from the rest of the chest – there are very complicated joints that are difficult to cut out of oak., which is the material Mehrman used for the rest of the chest, and likely the material that was used for most of the original.

Early American woodworking techniques are very different from modern ones, she said. Mehrman used many of the hand tools that the original craftsman did. On the original she saw plenty of evidence of tool marks: planes, chisels, scratch awls, dividers, etc., all of which help tell the story of how it was made. Her study and her work also demonstrated that the Strong chest was made by several people working on it at once – while Mehrman worked alone. “It took me a lot longer than it probably took them,” she said. “They weren’t fussy, they were making them fast,” she said. Even so, the chest was executed to a very high of skill, she said.

At every step, she said, she learned something new. “I wanted to reproduce the chest as closely as I could. The challenge was that every time I gained a new insight, I had to look deeper.” An example of that was her discovery about the front of the original chest. It has an unusual front, a type you don’t ordinarily see. I didn’t really understand this until I was working on the replica.” The joinery is different from the rest of the chest – there are very complicated joints that are difficult to cut out of oak., which is the material Mehrman used for the rest of the chest, and likely the material that was used for most of the original.

“I started to make the front out of oak. When I discovered how difficult it was, I realized the original maker probably made an intentional choice to use a less dense wood to simplify cutting the complex joinery.” While she can’t say exactly what wood was used on the front without scientific testing, she said it might be birth. Birch, beech, maple, and oak were all locally harvested, though it is not known whether the wood for the original chest was local.

Mehrman said it is clear from the grain on the wood that it was quartered from logs. Though there were sawmills here, she believes that the wood was more likely riven. Riving wood means to split logs into quarters, then split boards out of the quartered sections with hand tools. The experience of studying and making the chest was an honor and a privilege for Mehrman, she said. “As a maker in Northampton, I feel a real connection to this exhibition – I am living the theme “making it on Main Street,” she said. Mehrman has lived in Northampton for 21 years. “There is so much to learn in work like this – not just about materials culture but about social culture too,” she said.

In addition to making the reproduction chest, Mehrman also videotaped and photographed the process, and Making it on Main Street will include short videos with Mehrman’s commentary. “I think people will get a sense of not only my insights form making it but also about the process of hand-crafting furniture." Mehrman was quick to say how much the project meant to her. “For me this was bringing together my work and my love of museums and places that tell our history, especially local history.” she said.

Adapted from an article by Rachel Simpson the Daily Hampshire Gazette in the Gazette sponsored supplement,

Making it on Main Street: 400 Years of History, June 20, 2019.

Mehrman said it is clear from the grain on the wood that it was quartered from logs. Though there were sawmills here, she believes that the wood was more likely riven. Riving wood means to split logs into quarters, then split boards out of the quartered sections with hand tools. The experience of studying and making the chest was an honor and a privilege for Mehrman, she said. “As a maker in Northampton, I feel a real connection to this exhibition – I am living the theme “making it on Main Street,” she said. Mehrman has lived in Northampton for 21 years. “There is so much to learn in work like this – not just about materials culture but about social culture too,” she said.

In addition to making the reproduction chest, Mehrman also videotaped and photographed the process, and Making it on Main Street will include short videos with Mehrman’s commentary. “I think people will get a sense of not only my insights form making it but also about the process of hand-crafting furniture." Mehrman was quick to say how much the project meant to her. “For me this was bringing together my work and my love of museums and places that tell our history, especially local history.” she said.

Adapted from an article by Rachel Simpson the Daily Hampshire Gazette in the Gazette sponsored supplement,

Making it on Main Street: 400 Years of History, June 20, 2019.